Dubbing in Syria: A Vocal Art Immortalized in the Memories of Generations

Syrian dubbing wasn’t just a tool for dialogue, but an entire art that added a new soul for international works. Due to the professional acting, the fluent Arabic spoken, and

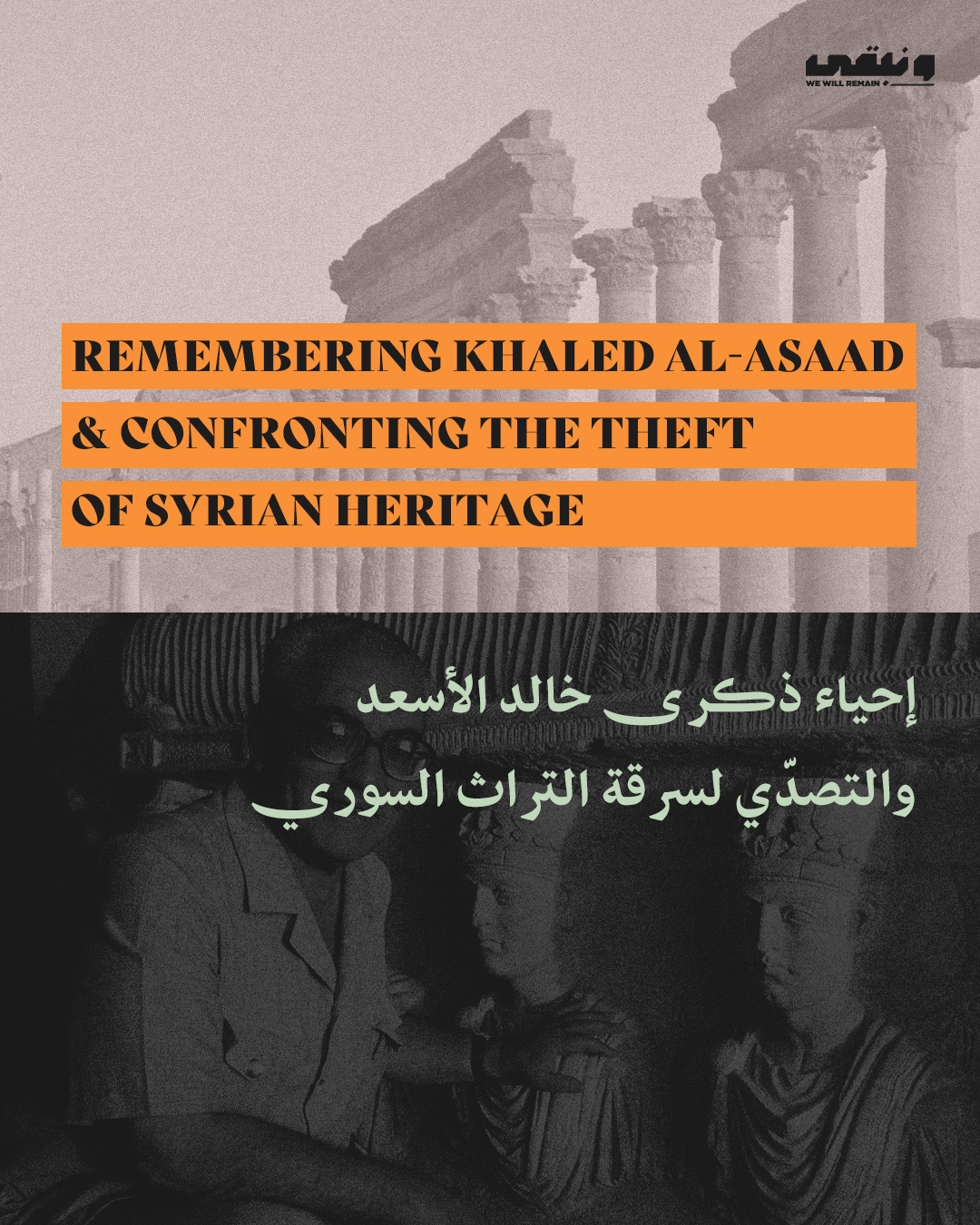

One of Syria’s most renowned archaeologists, Khaled Al-Asaad, was killed by ISIS almost ten years ago for refusing to betray his beloved Palmyra. He grew up in Tadmur and worked for more than 40 years to preserve, restore, and excavate the old city’s ruins. Before he became a target of radicals, his life’s work served as tribute to Syria’s cultural essence. Al-Asaad returned to his hometown to devote his life to the preservation of Palmyra after graduating with a degree in history from Damascus University. By working with archaeologists around the world, he raised awareness about the site on a global scale. The world was able to learn the mysteries of Palmyrene by deciphering and translating its inscriptions thanks to his proficiency in ancient languages like Aramaic.

Al-Asaad actively discovered new facets of the ancient city in addition to performing maintenance. He oversaw excavations that turned up underground cellars, Roman-era cemeteries, and even a rare Byzantine burial site in the museum’s garden in Palmyra. His meticulous documentation turned forgotten ruins into living history.

Once the prosperous capital of a desert empire ruled by Queen Zenobia, Palmyra was more than just stone. It represented Syria’s historical affluence with its imposing colonnades, agorae, arches, and temples. However, because of its magnificence, it became a target for those who sought to alter or obliterate history, particularly religious fanatics who saw its artifacts as heretical. Al-Asaad handed up his duties to his son Walid after retiring in 2003. However, he continued to be active and had a strong connection to Palmyra’s destiny even after retiring. Al-Asaad remained in the city after it was taken over by ISIS in 2015, hoping that his presence would prevent more damage. He would die as a result of that bravery. Al-Asaad’s death was not an isolated tragedy. It marked a turning point in a larger war against cultural memory.

History itself became a casualty of the violent, disorderly atmosphere created by the Syrian conflict. Extremist groups directed their wrath against identity and heritage during conflicts over territory and power. In addition to battling individuals, they were destroying the history, ideals, and symbols that constituted national pride.

The destruction of monuments was staged and documented by ISIS. They destroyed Assyrian sculptures in Mosul. They destroyed the famous Arch of Triumph and the Temple of Bel in Palmyra. These actions were deliberate attacks against memory and proof of coexistence, tolerance, and pre-Islamic past rather than haphazard ones.

The then-UNESCO Director Irina Bokova made the urgent plea, “Heritage belongs to all humanity.” She urged educators, artists, and journalists to protect the cultural heritage of the world. However, the struggle to protect cultural legacy was more than just a symbolic issue for many Syrians, including Khaled Al-Asaad. It was achingly real and very intimate.

Al-Asaad, who was captured in August 2015, was tortured for a month. He was publicly executed and paraded through the ruins he had once guarded, refusing to give up the whereabouts of buried antiquities. Five “charges” were read out against him by a terrorist: he was the “director of idols,” he travelled to Iran, and he served in the government. His passing delivered a terrifying message: there is a price for rebellion.

ISIS was unable to obliterate Khaled Al-Asaad’s legacy in spite of their savagery. He received posthumous recognition as a “Monument Man” and hero. He was awarded the Ordre National du Mérite in France, the Civil Merit Medal in Syria, and comparable honours from Poland and Tunisia. Around the world, archaeologists, historians, and ordinary people were inspired by his story.

Thousands of other valuables were stealthily taken and sold while monuments were demolished in public view. Ancient Syrian cities including Mari, Apamea, and Dura-Europos have been destroyed since 2011.

Syria lost 5,000 years of cultural legacy when coins, mosaics, and statues were stolen and used to finance military organizations. Satellite photos taken in 2014 showed how much damage had been done in Apamea. It was damaged by around 4,000 looting trenches. Mari’s cuneiform tablets were removed from the palace walls. These items become disjointed pieces of memorabilia without a backstory and in the absence of documentation or context.

Not every looter is created equal. Some are poor villagers trying to make ends meet. Others participate in formal networks of smugglers. Looting was regulated under ISIS, replete with permits, excavation crews, and taxes. Destroying culture turned into a corporate strategy. Once home to many ancient sites, Deir ez-Zor was mined by ISIS for relics that might be sold. Later, ISIS files that revealed an official “Antiquities Division” were found by American forces. In one instance, a single spot yielded goods valued at $1 million. Theft of heritage turned into a source of income alongside oil and ransom.

Not all artifacts remain in Syria. Through Lebanon, Turkey, and Iraq, smugglers transport them to the US, Europe, or the Gulf. In 2019, Germany seized a palmyrene bust that had been transported through Lebanon under false pretences of being Jordanian. The second life of stolen history is hidden here. The plundering continued even after ISIS lost its area. The trade is carried out by local warlords, criminal gangs, and occasionally military organizations. Using earthmovers and metal detectors, today’s looters stealthily resell culture on the illicit market.

Smugglers create false histories in order to pass off stolen goods as legitimate. They produce papers stating that antiques came from historic British or Swiss collections. Fake excavation records were used to sell one Roman mosaic from Homs in the United States. Crime becomes business through forgery.

Today, looting has shifted to the internet. Posts offering recently stolen artifacts—often include GPS information or images from the excavation site—abound on Facebook and Telegram. According to the 2020 Athar Project, there are dozens of Arabic-speaking organizations with tens of thousands of members who engage in open illegal antiquity trade.

The loss of Syria’s cultural legacy is a worldwide tragedy, not a local one. Khaled Al-Asaad sacrificed his life to protect a universal human narrative. The message is obvious from Palmyra’s stillness to the ruins of Ebla: remembrance must be preserved. Fighting for the future means preserving the past.

Syrian dubbing wasn’t just a tool for dialogue, but an entire art that added a new soul for international works. Due to the professional acting, the fluent Arabic spoken, and

Discover the majesty of Khan Asaad Pasha, the largest caravanserai in Old Damascus. Built in 1751 and declared a historical landmark in 1973, this architectural marvel has undergone significant reconstruction,

I have always wanted to do this: get in my car, call my friends, pick them up, and hit the road. “Where do you wanna go?” I want to ask,